The Forgotten Visionary of Women's Fashion

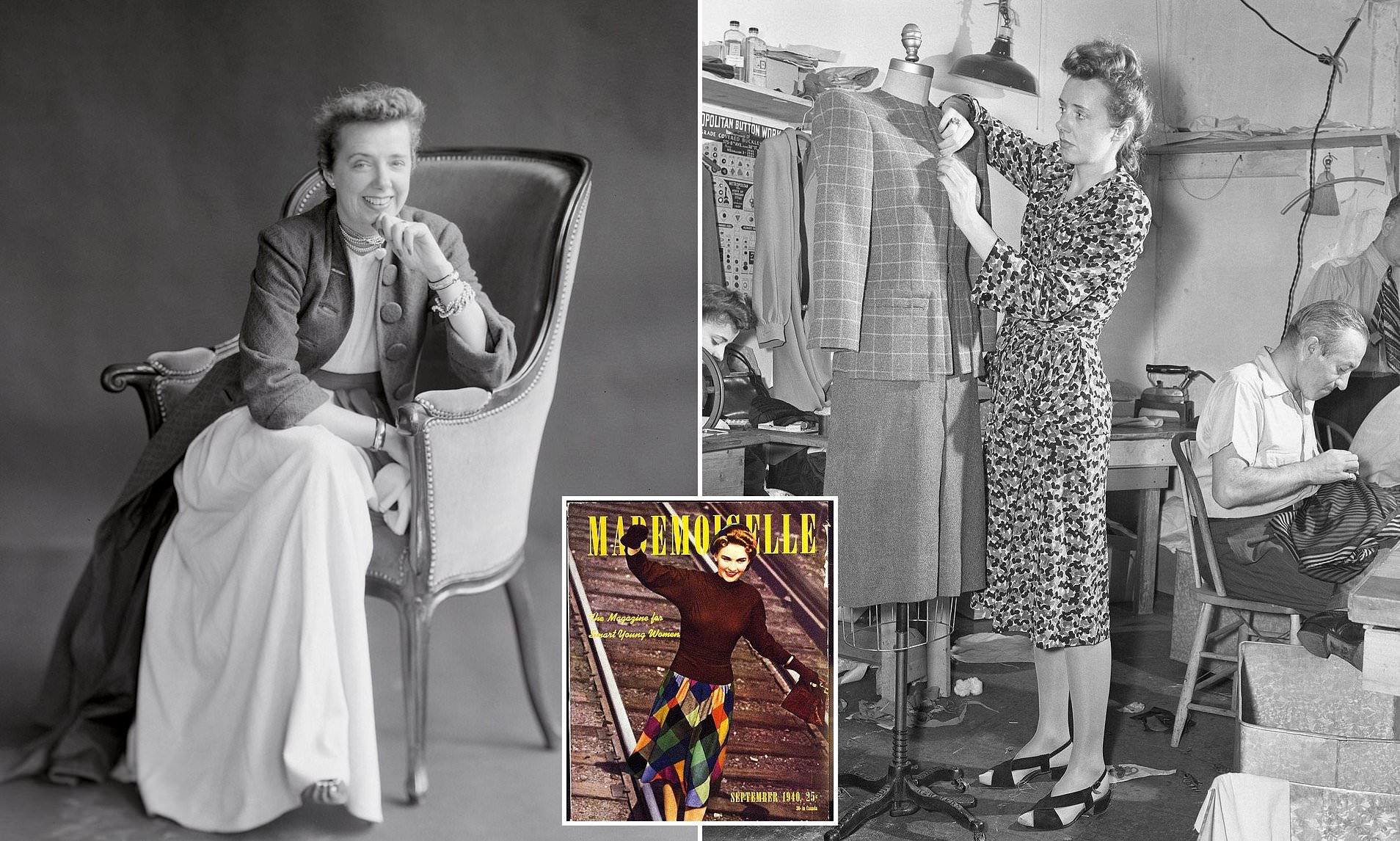

Every time a woman puts her hands in her pockets, zips up the side of her pants, or belts the waist of her wrap dress, she owes a debt of gratitude to someone she has likely never heard of. That someone is Claire McCardell. She was once one of the most influential and famous fashion designers in the world. When she died in 1958, her obituary was featured on the front page of a major newspaper, where she was hailed as the 'All-American designer for the All-American girl.' Yet, despite having more of an impact on women’s lives than Coco Chanel and Christian Dior combined, McCardell has been largely forgotten—known only to fashion experts and design historians.

Author Elizabeth Evitts Dickinson is determined to change that. With her new book, Claire McCardell: The Designer Who Set Women Free, she aims to reinstate McCardell in the pantheon of designer greats. According to Dickinson, what McCardell did entirely reinvented the way women dress.

A New Era of Women’s Fashion

McCardell came to prominence in the 1930s and 1940s, during a time when women's lives were changing rapidly. They were living, moving, and working in a modern world. McCardell turned her nose up at corsetry, high heels, and delicate fabrics, advocating instead for a feminist philosophy that translated into designs she believed a liberated woman would want to wear.

"You have to design for the lives American women lead today," she noted in an interview with feminist writer Betty Friedan in 1947.

Born in 1905 in Frederick, Maryland, McCardell was the daughter of a banker and housewife. As a girl, she railed against the restrictions of female clothing that made climbing trees and stashing apples almost impossible. She majored in home economics for two years at Hood College before making the bold leap to New York City to earn a degree from the New York School of Fine and Applied Art (now Parsons The New School for Design).

A stint in Paris convinced McCardell that American women deserved better than the poor imitations of Parisian haute couture that filled U.S. stores. She believed they needed clothes that reflected the pioneering spirit embodied by Charles Lindbergh, whom she watched land at Le Bourget Airport after his historic solo flight from New York to Paris.

Innovations That Changed Women’s Lives

Returning to New York and its Seventh Avenue design district—the hub of American fashion production—McCardell secured a job at Townley Frocks, then one of the leading garment manufacturers. During her tenure, she fought for the inclusion of many of what we now consider staple features in womenswear.

Pockets rather than purses was an essential ethos in the McCardell worldview. Not content with the male-driven view that they made the female figure look fat, the designer argued pockets were a necessity for women whose presence in the modern American workforce was becoming ever more important.

Closures were next on her list. Without a husband or maid, how could a woman fasten her dress? Without further ado, she shifted the zipper on her pieces from the back to the side. That change embodied how the designer believed women should be allowed to dress—'independent clothes for the independent working gal,' she proclaimed.

According to her boss at Townley, her pleated 'monastic dress,' created in 1938, looked terrible on the hanger but, when belted at the waist with its spaghetti-style ties—a design innovation—embodied functional elegance that made it an immediate bestseller when it hit the ready-to-wear racks.

Four years later, McCardell bested her own record for success when, in 1942, she created the cotton 'Popover' wrap dress. It was marketed as the 'original utility fashion' and sold for $6.95. The dress was originally made from inexpensive cotton, which McCardell later switched out for denim—a bold move and a novel use of a fabric previously considered the reserve of menswear.

A Legacy That Endures

Thirty years before Diane Von Furstenberg repurposed the wrap dress into one made from jersey, McCardell's 'Popover' gave women the benefit of looking good while still being functional. Lord and Taylor, the famed department store, gave the dress an entire window display in its flagship store on New York's Fifth Avenue. One fashion journalist described the life-altering garment as 'so glamorous that Fifth Avenue and the farm united in their acceptance of it.'

A staggering 75,000 dresses were sold in the first six months, earning McCardell not just fame but her place as the preeminent arbiter of female fashion.

Cut off from the leadership of Parisian fashion houses due to World War II, she was allowed to flex the muscles of innovation without the backlash of the conservative male voices that still dominated American fashion. Trousers with pleats, and yes pockets, became de rigueur for a newly functional face of the female workforce, who also found in McCardell's love of hoods a practical replacement for hats which remained in place only with uncomfortable and unstable pins.

Leggings and other sportswear separates quickly became part of the McCardell repertoire. Faced with a shortage of leather due to wartime rationing, she had the perfect excuse to abandon the high heel, which she had long thought impractical for a working woman. She pivoted to the ballet flat—soles made of rubber and the shoe made from a fabric matching her designs.

Though she sparked a trend that still flourishes today, her rival Coco Chanel is the one who gets all the credit, despite the fact the French designer didn't launch her own version until 1957.

But, while McCardell thrived during the war with her penchant for utilitarianism, she found herself distinctly out of step with a post-war return to the whimsy of impractical glamor. In February 1947, Christian Dior debuted the 'New Look.' Padded shoulders, tightly corseted waists, high heels, and impossibly full skirts filled out a collection that was the antithesis of all that McCardell had worked for in her now two-decade career.

Romantic and ethereal, Dior's designs captured a much-needed emotional rejuvenation after the deprivation of the wartime years. The post-war resurgence of French couture was still in full swing when, in 1958, McCardell died at the age of just 52.

Buyers of the American fashion emporiums had returned to copying Parisian couture, and American talent lay dormant for nearly two decades until a new wave of designers—such as Calvin Klein, von Furstenberg, Halston, Donna Karen, and Ralph Lauren—emerged.

But it wasn't just the mood of the time that contributed to McCardell's fall from favor. In truth, she contributed to the end of her own line for the simple reason that, unlike Chanel and Dior, she did not designate a successor. Head designer Yves Saint Laurent carried the Dior label to greatness following Christian Dior's death in 1957. But McCardell's label, whose ownership reverted to her Maryland-based non-fashion family, died just a few months after she did.

As a consequence, few acknowledge McCardell's place as one of history's fashion greats. Does Anna Wintour even know her name? Maybe, but my hunch is probably not. For a woman who has championed fashion at its most exclusive, restrictive, and expensive, Wintour would surely find little to admire in McCardell's functional utilitarian designs.

But the reemergence of McCardell's name is a timely reminder that the history of dress is ultimately shaped by how the majority of women have lived in and loved their clothes. Because she may not have been embraced by the fashion glitterati, but McCardell's legacy is alive and well—and it's woven into the fabric of every woman's wardrobe today.

Posting Komentar